2 April 2025

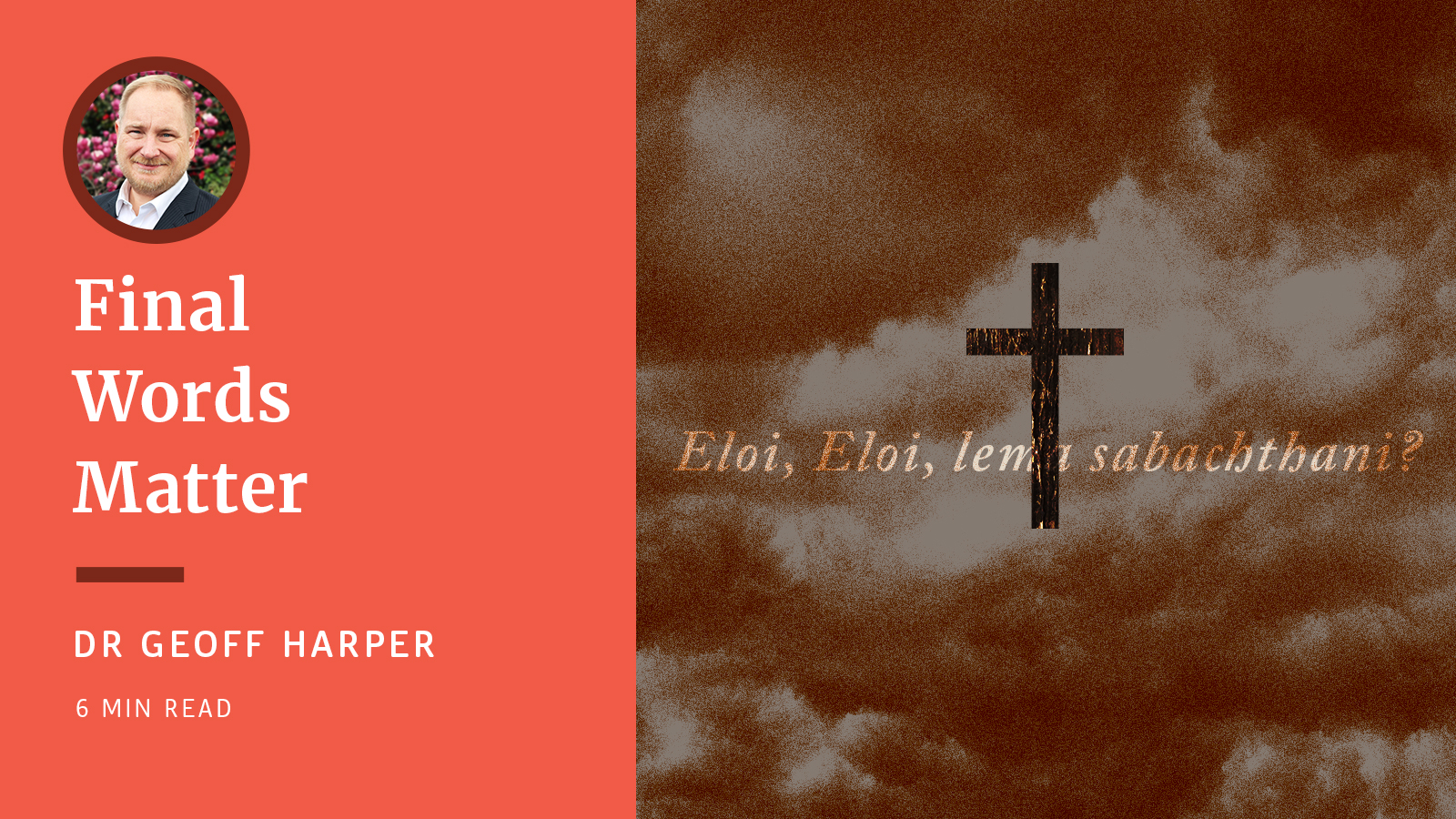

Final Words Matter

Geoff Harper

Final words matter.

In an airport departure lounge, with a grown child about to leave home, at the bedside of a loved one, we strive to find the right thing to say. Because parting farewells are precious. Recalling those moments, even years later, stirs deeper memories that evoke a person’s life and significance.

Final words matter in the Gospels too. Matthew and Mark, in recounting Good Friday, carefully note the last thing Jesus said. They remember that as he hung on the cross, close to death, he cried out in a loud voice, “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?” (Matt. 27:46; Mark 15:34). The words repeat Psalm 22:1 exactly, making this one of the best-known verses in the Psalter.

Moreover, Mark records Jesus’s words in Aramaic (“Eloi, Eloi, lema sabachthani?”) to make sure we understand these are the very words he used.[1] But why, in that final moment, did Jesus quote a psalm? More pointedly, Why did Jesus wail in lament?

"But why, in that final moment, did Jesus quote a psalm? More pointedly, Why did Jesus wail in lament?"

Luke’s Gospel only sharpens the question. There, Jesus’s last recorded words also come from a lament psalm: “Into your hand I commit my spirit” (Luke 23:46; Ps. 31:5). In fact, in the Garden of Gethsemane, Jesus had already taken up the laments of Psalms 42 and 43 as he moaned, “My soul is overwhelmed with sorrow” (Matt. 26:38; cf. Ps. 42:5, 11; 43:5).

But why is Jesus lamenting? Don’t his suffering and death represent the climax of God’s plan of salvation? Isn’t this what the Law and Prophets eagerly anticipated? Surely this is a moment for praise, for thanking God. Why, then, lament?

Jesus laments because Easter Sunday is still a future reality. Before that glorious day of joy and exultation come suffering, death, and burial. In such dire circumstances, Jesus is right to lament because that is what the godly do. While in English parlance, lament can simply indicate a loud howl or a passionate expression of grief, lament in the Bible has a more technical sense. Lament is “more than sorrow or talking about sadness. It is more than walking through the stages of grief. Lament is a prayer in pain that leads to trust.”[2]

"Lament is a prayer in pain that leads to trust."

So, Jesus prays Psalm 22:1. Not because those words belong only to him, or because they are a prophecy about him. The heartrending shout that emanates from the cross is Jesus’s recognition that God invites his people to use the psalms of lament as their prayers in pain whenever circumstances demand it. By including Psalm 22 in Scripture, God bids the God-forsaken to question him directly: “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?”

While it might be tempting to believe that the time for such raw expression ended at Golgotha, that would be an exercise in denial. It would deliberately ignore the ongoing use of lament in the New Testament—including the apostles grappling with the aftermath of Judas’s betrayal in Acts 1:15–20 (cf. Pss. 69:25; 109:8) and Paul conceptualising the suffering of believers as sheep destined for slaughter (Rom. 8:35–36; cf. Ps. 44:22). It would also disregard centuries of lament in Jewish and Christian spirituality and diminish the sorrow present in the pew each Sunday.

Nevertheless, this kind of denial is everywhere present. One can glimpse it in the rebranding of funerals as “celebrations.” It emerges in a diet of sermons and songs that exude unqualified confidence and certainty—celebrating life in a major key. Its shadow looms as the broken and grieving disengage from church, never to return. Followers of Jesus, unlike Jesus himself, are sometimes overly quick to move to resurrection. Yet, by forgetting, or even deliberately suppressing, the realities of suffering, death, and burial in our gatherings, we can end up espousing a form of Christian Buddhism. The result is deleterious: by censoring suffering, we also censor sufferers.

"The antidote is to cultivate a practice of individual and corporate Christian lament."

The antidote is to cultivate a practice of individual and corporate Christian lament. This is vital for many reasons.

First, lament is a necessary exercise in truth-telling. Western culture displays an ingrained distaste for weakness and suffering and excels in fabricating a steady stream of suppressants: more work, more medication, more alcohol, more music, more Netflix; anything to drown out the encroachment of death in all its various guises.

The psalmists chart a different path. They model turning to God to complain about circumstances as they really are, without lessening or denying their horror. They protest, “How long?” They implore, “Why?” This is precisely what Jesus does. His commitment to truth-telling prevents an exclamation of “Praise God!” from the cross. Accordingly, Walter Brueggemann observes, “It is clear that a church that goes on singing ‘happy songs’ in the face of raw reality is doing something very different from what the Bible itself does.”[3]

"Yet, the psalmists, by their determined pinioning of God in relation to suffering, display a profound and unshakable belief."

Second, lament upholds the sovereignty of God. Indeed, the degree to which the laments’ copious second-person questioning of God (“you”) feels uncomfortable, reveals the degree to which we underplay God’s control over all things—the bad as well as the good. It’s much easier, and can appear more pious, to blame parents or society or circumstances or the church. Yet, the psalmists, by their determined pinioning of God in relation to suffering, display a profound and unshakable belief. So much so, that even when enduring God-forsakenness, the author of Psalm 22 still turns to God. That is faith; that is worship.

Third, lament gives the grieving a voice in the darkness. Other responses to desperate times—silence, anger, withdrawal—are declared acts of unfaith. Instead, God encourages his people to utter words of lament as prayers in pain. In this way, the psalms become instructors, granting words when we have none, teaching us what to say and how to say it. By reusing these words, the laments also lead us through a process of turning to God, complaining to him, pleading for deliverance, and declaring ongoing trust—not because suffering, doubt, and grief have ended, but in spite of their lingering presence. These are words suited for Holy Saturday, for life in the in-between, as we too await resurrection.

"This is a poem, a song, a prayer to be used by the gathered community of God’s people."

Finally, lament enables us to mourn with those who mourn until that final day. This is exactly what the Apostle Paul expects Christian communities to do (Rom. 12:15). Yet, the communal necessity of lament is often missed, despite frequent reminders in the psalms. Even Psalm 22, with its highly personal expressions of pain, opens by noting instructions for “the director of music.”

This is a poem, a song, a prayer to be used by the gathered community of God’s people. Its words are necessary precisely because there are those present who feel God-forsaken, who on any given Sunday are weighed down by the burden of the question that plagues the author of Psalm 22:1: “Why are you so far from saving me?” Lament is something to do together. Praying, preaching, and singing these words allows us to stand in solidarity with the hurting and the grieving, learning to lament with them and for them as we pray in and through the pain as a corporate expression of trust in the God who is sovereign over all.

Good Friday marks an opportunity to pause and reflect. Exultation fades as the horror of sin is encapsulated in a forlorn cry of God-forsakenness from the cross. That is what our culpability required. That is what the love of God was willing to do. By recording that exclamation, Matthew wants us to understand that, at the cross, God was holding back from delivering Jesus. That Jesus was not seeking his own deliverance. Rather, Father and Son chose to suffer for the sins of the world. Yet, in that moment of anguish, by reusing Psalm 22, Jesus also validates lament as a right way of speaking to God. And, like the psalmists, he encourages emulation. For Jesus, as much as the Gospel writers who biographized his life and death, final words matter.

Geoff Harper

Director of Research; Lecturer in Old Testament

[1] Walter Brueggemann, Into Your Hand: Confronting Good Friday (Eugene: Cascade, 2014), 17.

[2] Mark Vroegop, Dark Clouds: Discovering the Grace of Lament (Wheaton: Crossway, 2019), 28.

[3] Walter Brueggemann, Spirituality of the Psalms (Minneapolis: Fortress, 2002), 26.